Decision Making in Early Stage Teams

Much has been written about the various frameworks and strategies for launching and scaling products. But the real challenge is knowing which frameworks to apply and what problems to prioritize on a daily basis, which requires sound judgment. Often, the advice that truly matters is super specific to a startup’s context as markets keep evolving and every moment in business happens only once. Hence, one has to glean insights from other people’s experiences and adapt those insights to their own context. This is where diverse teams help unlock the power of their collective perspectives. When done right, the whole becomes greater than the sum of its parts. But it’s easier said than done. With that in mind, I hope you find this post useful. It is something that I wanted for myself when I was working in early-stage teams.

Early Stage Dynamics

Working at an early-stage startup feels like being part of a tribe! There is this shared vision of the future that the team believes in but the outside world hasn’t embraced yet. This gives rise to a tribe-like dynamic where there are certain myths or cultural truths that the tribe believes to be true. These shared beliefs are important for maintaining social harmony within the group. Questioning these usually leads to cognitive dissonance in the tribe which the tribe members then knowingly or unknowingly act in ways to resolve the dissonance. Below is one extreme example where the ‘troublemaker’ got expelled from the group, but you get the point (more).

Older members, thus, act as custodians of ‘tribal knowledge’. They have more context - one that’s not usually documented anywhere but is shared through osmosis- organically- while assimilating new members into the group. However, the longer one has been part of a tribe, the more it becomes part of their identity. As a result, the biases that can distort one’s perception of reality when faced with data that challenges tribe’s core beliefs tend to be stronger in older members as compared to newer members in the tribe. Sometimes, the incentives can be such that even if tribe members know the truth, they don’t want to accept the truth or say it out aloud. This is because questioning the cultural truth can come across as the sign of being a ‘non-believer’ which then gets in the way of working together as a team towards the shared vision. But when unchecked, this disconnect from reality can grow over time and lead to undesirable outcomes that no one benefits from in the long run. It is, therefore, especially important for Founders to create mechanisms (formal or informal) that will help the team get to the truth in times of disagreement without disturbing the social harmony of the group.

Amazon created these mechanisms by using their Leadership Principles in everything they do, from hiring to everyday decisions. Netflix too has its own way of creating High Performance Teams. Creating and managing culture is a fascinating topic of its own. But here I wanted to share something more tactical. Something more specific that I have observed time and again i.e., the importance of truth-seeking in early-stage teams.

The Core Idea - Name It to Tame It!

After working on two early-stage tech products and with a few early-stage founders, I’ve found that truth-seeking is too important to be left to its own devices in the initial days. Truth can be uncomfortable; it’s one of those “simple, not easy” things when it comes to actually practicing it. We all think we are rational creatures who see things objectively and know how to handle negative feedback, but in reality, we are emotional beings, prone to individual biases that shape how we perceive our reality. For these reasons, we rely on others— Advisors, Executive Coaches, Personal Boards of Directors, or simply Friends— to help us get closer to the truth. I have therefore been curious about how one could design a team for truth-seeking and shape the team’s culture to foster constructive conflicts that increase the chances of a successful outcome.

On a meta-level, I believe the key to making better decisions lies in getting the team on the same page and speaking the same language. Since truth can be uncomfortable and may upset people, it’s crucial to establish a shared vocabulary beforehand— one that can be used to communicate when there’s a risk of team members becoming defensive or upset. It’s much like using a pre-agreed meme to cut through the noise! This basic idea can be applied in various ways, depending on what a team feels is important to be mindful of. Below, I share three examples relevant to early-stage teams, though they can be adapted to any context.

Example-1: Creating Shared Vocabulary To Avoid Biases

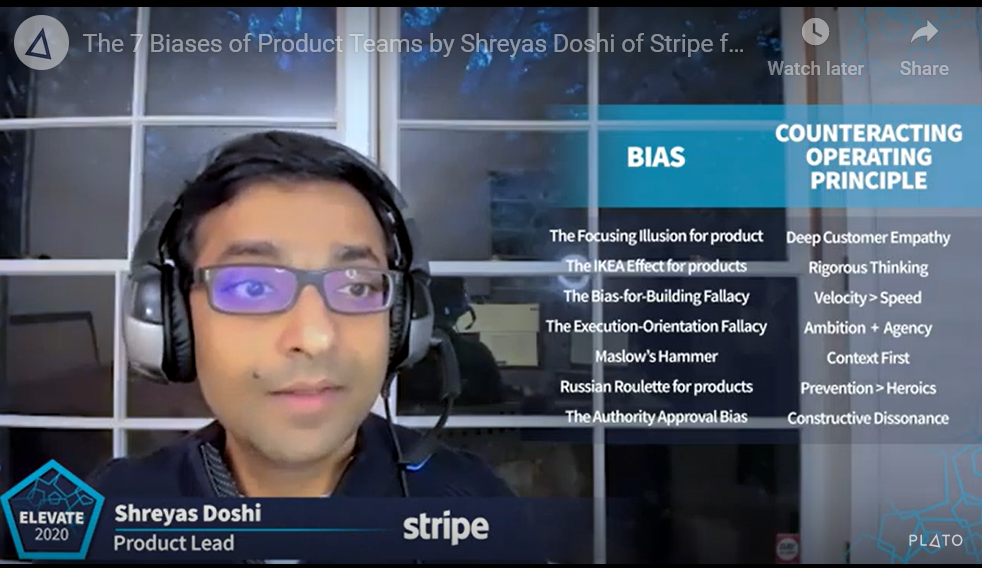

This video is 20 concentrated minutes of wisdom from Shreyas Doshi! If you’re an early-stage founder working on a startup idea for the first time, do watch it once— and then again until you’ve fully internalized it (you can thank me later!). It’s one of those things that’s easy to overlook unless you’re actively seeking it, which often means the problem has already surfaced and valuable time has been lost. While practicing mindfulness helps on an individual level, socializing this shared vocabulary within your team early on is a great way to catch these biases sooner rather than later. The screenshot below summarizes the 7 biases and how a team could counteract them.

Example-2: Creating Shared Frames and Shared Vision For Better Alignment

In the early days, founders are typically laser-focused on customer discovery. Guiding principles like “Build something people want”, “Do things that don’t scale”, and “Ignore your competitors” are something to live by in the early-stages. But they can also trap teams in cycles of execution that overlook the bigger picture. Teams can over-index on “Talk to users, write code” and risk missing the forest for the trees. YC’s essential startup advice also highlights the importance of strategy, with notes like “Startups can only solve one problem well” and “Sometimes you need to fire your customers (they might be killing you)”. However, these lessons often get overshadowed in the rush to execute —especially by highly technical founders who may prefer to “just build the thing” in a day or two rather than “wasting time” pondering whether it should be built at all.

When teams struggle to define their target customer or strategy explicitly, it signals a need to pause and align on higher-level priorities. Usually when discussions related to target customer (and strategy) are going in circles, that’s because these elements aren’t clearly documented. As a result, individual members are coming at a given problem with their own internal frames and those implicit frames are colored by individual biases and assumptions. Having shared frames makes different implicit considerations explicit and enables labeling of potential biases and assumptions. This enables better perspective taking and creates space for fruitful discussions, leading to better choices and alignment. For example, Shishir Mehrotra’s article on Eigenquestions provides excellent tools for framing problems collaboratively. Techniques like framing diagrams and team-driven framing exercises can help teams align on the “right” questions to guide their efforts.

It’s tempting to kick the can down the road on strategic questions like “What’s our source of competitive advantage?” Understandably, there are more urgent problems in the early days. But ignoring these questions risks implicit strategies taking over—often with conflicting priorities. Having a shared vision, documented and articulated, aligns the team and helps them work backwards from a clear goal. A strong shared vision outlines not only what success will look like for customers but also how success is likely to impact the industry, providing guidance without overcommitting to a specific path.

Importantly, it’s okay to be wrong in the early stages—afterall the customer discovery phase IS about learning and adapting. But without making assumptions explicit, teams may miss the chance to course-correct in time. Explicit frames and shared visions not only help avoid this but also keep teams focused on the forest, not just the trees.

Example-3: Creating Shared Nomenclature To Communicate Complex Ideas

I’ve yet to come across a good resource that summarizes the hundreds of mental models collected by Farnam Street and James Clear. However, I believe this is another instance where having a shared nomenclature is incredibly helpful. To be clear, this doesn’t necessarily have to be restricted to the models mentioned here. It can be extrapolated to frameworks, habits, and more.

Since we’re discussing early-stage teams, I’d like to share one specific framework: the Cynefin Framework, which I think is particularly helpful for first-time founders. The Cynefin Framework is a useful way to remind people to be mindful of their current context when they fall into their old habits and patterns. Humans are creatures of habit, and if someone is used to working in one context (say, a big company), it can take time to adjust to another (like an early-stage startup)— and vice versa. Different things are rewarded at different stages. For example, in the early-stage, it’s not about scaling and building things perfectly; it’s about experimentation and rapid learning (and that’s why truth-seeking is all the more important!)

Case Study: Airbnb borrowing inspiration from Disney

Because truth-seeking is not natural, the onus is on Founders to create mechanisms to gather inputs from different stakeholders and improve their decision-making. One such example is of Brian Chesky launching “Project Snow White” to align the early team at Airbnb around important problems to create an engaging user experience. He did this by storyboarding the entire user journey and capturing critical moments in a few frames that highlighted what the guests and hosts were going through. Having these shared frames helped everyone to contribute their diverse perspectives and institutionalize otherwise unwritten knowledge. These frames probably not only helped the team at the time but also served as an important cultural artifact as the company went through its hypergrowth phase. You can get a glimpse of the process here.

I hope you found this information helpful! In closing, I want to highlight that implementing these ideas can still be quite challenging. After all, we are creatures of habit, and our attention is often divided. To truly make these principles stick, it’s essential to weave them into team rituals and the overall culture. But that’s a discussion for another time!